Who are the Imazighen?

History of the Imazighen

To download this film (which is in French), click here (MP4, 1 file, 411 MO).

Histoire des Imazighen from tamaz video on Vimeo.

History: Amazigh Roman Emperor

Septimus Severus–Amazigh Roman Emperor

“Septimius Severus (Latin: Lucius Septimius Severus Augustus; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211), also known as Severus, was a Roman Emperor [of African (Berber) origin] from 193 to 211. Severus was born in Leptis Magna in the province of Africa.”

For more information, see the following link (from which came the above paragraph):

Tifinagh by video

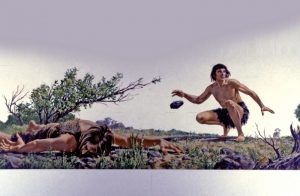

The crow

At the beginning of the world, the crow was white. The Prophet, may God bless him and save him, sent to him and said, “Here’s gold. Give it to the Muslims. And here’s lice. Give it to the Europeans.”

So the crow got up and gave to the Europeans the gold, and he gave to the Muslims the lice. To punish him, God changed his appearance, and his feathers became black. When he speaks he says, “Aq, Aq,” that is, “That serves me right! I betrayed a trust.”

This text is taken (and adapted) from E. Laoust, Cours de Berbère Marocain: Dialecte du Maroc Central, Paris, 1939, p. 240, numéro 1.

Tamazight Language

Tamazight-French Dictionary (Tamazight of Central Morocco)

Author: Miloud Taifi

Tamazight-Arabic Dictionary

Author: Mohamed Chafik

Tamazight and Tifinagh Links

Download the Tifinagh alphabet from the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture (IRCAM)

Amazigh School: games for learning the Tifinagh alphabet and Tamazight words

Listen to the Tifinagh alphabet.

Swathmore.edu: linguistic bibliography of Tamazight

Wikipedia articles:

Request for a Wikipedia in Tamazight

Bibliomonde.com: the languages of Morocco

Ircam’s Tifinagh ChartTifinagh Chart – Ircam

Amazigh proverbs

Amazigh Proverbs from the Newspaper Agraw Amazigh

Those Before Us Have Spoken

Our ancestors didn’t leave us anything to say; they’ve said it all.

1. Today at your place, tomorrow at mine.

Emphasizes the need to help each other, since we are all vulnerable to the same types of problems.

2. Weaving at night brings a big laugh in the day.

Weaving at night (when you can’t see) results in a laughable outcome (which you only realize when the daylight comes). If you don’t work/buy/etc. in proper conditions, the outcome will be less than desirable.

Amazigh Riddles

Click a question to read the answer.

1. Nzerx-ac-tt-i-n: La ttawi awal, ur da tsawal.

I’ve got one for you: It takes a word but it doesn’t speak. What is it?

2. Nzerx-ac-tt-i-n: Ibbi yaman ur immiɣ.

I’ve got one for you: It crossed through water but didn’t get wet. What is it?

3. Nzerx-ac-tt-i-n: Ur da ttaru ɣas s isfuruḍen.

I’ve got one for you: It gives birth only by kicks. What is it?

4. Nzerx-ac-tt-i-n: La-s iddal iswi, ur da-tt ittasi ulɣem.

I’ve got one for you: A simple basket covers it, but even a camel can’t lift it. What is it?

5. Nzerx-ac-tt-i-n: Ilula-d s tamart, immut bla tamart.

I’ve got one for you: It was born with a beard but died without a beard. What is it?

6. Nzerx-ac-tt-i-n: Tegdem da ur tenɣil.

I’ve got one for you: It turned upside down but didn’t spill. What is it?

Amazigh culture has a tradition of riddles. These riddles are told with a specific formula, somewhat like the English: “What’s black and white and read all over? A newspaper.” First, an introductory phrase is given, announcing “I’m going to tell you a riddle.” Then one or two short statements are made. These are not framed as questions but as statements. However, it is implied that the listener must then guess what object is being described by the cryptic statements.

The introductory phrase is:

Nzerx-ac-tt-i-n

nzerx + ac + tt + i + n

first person indirect object direct object “i” sound “n” of farness

singular “past” pronoun: 2 m.s. pronoun: 3 f.s. added for

conjugation of “to you” “it,” that is, pronunciation

the verb “nzer” the riddle

Notice the presence of the indirect and direct object pronoun as well as a direction particle all with one verb. The only thing that changes in this introductory phrase is the indirect object pronoun, which may be ac , am , awen , or awent depending on who is being addressed. The verb nzer here functionally means “to tell a riddle” and technically means just “to tell”: “I tell it to you.”

There are some regional variations: some areas use the masculine third person singular direct object pronoun t (without the doubling of the consonant) instead of the feminine tt ; when that is used sometimes the i for pronunciation is not added; some regions use slightly different indirect object pronouns (like ak , with a hard or a fricative “k” sound, instead of ac ); and sometimes there are some slight changes to the verb. Some regions use ɣ instead of x for the first person singular verb ending. Some regions also modify some of the verb consonants or use a different verb. There are at least five variations: bzer , zunzer, zuzzer , ḥeji , and qqen.

So, you say the introductory phrase. Then you say the cryptic statements. You can leave it at that, or you can add a phrase like: Mag-gmes? or Matta ntta? (What is it?) or Ini mag-gmes or Ini matta ntta (Say what it is.). Remember if the “it” you are talking about is feminine or plural, these questions change to things like:

May tmes? or Matta nttat? etc., according to the gender and number of the “it.”

Most of these traditional riddles are virtually impossible for an outsider to guess correctly. They often involve intricate details of agricultural and nomadic life.

Ddan-d iwaliwen-ad zeg E. Laoust, Cours de Berbère Marocain: Dialecte du Maroc Central, Paris, 1939, p. 269.

1. tabratt a letter

Return to top of page

2. amalu a shadow

Return to top of page

3. tagmart a mare

Return to top of page

4. tasraft an underground storage area

Return to top of page

5. agertil a reed mat

Return to top of page